Chef Flynn McGarry knows what he likes and what he does not like. He likes very small drinking glasses (“it feels like you’re accomplishing something”). He likes good tailoring. He likes JFK (the president, not the airport), and the city of Copenhagen, and Sara Delano Roosevelt Park (“I’ve never seen a park that literally has barbed wire in it!”). What he does not like, I have just learned, is the word casual. We are at the Four Horsemen, James Murphy’s Brooklyn wine bar, eating melty little rounds of hanger steak with grilled asparagus in orange romesco pools. It’s the kind of relaxed, drop-in-when-you-feel-like-it, blond-wood-tabled restaurant that most people would call … casual. But when you describe a restaurant as casual, McGarry tries to tell me, what you are really doing is describing something else.

“To me, a casual place, you don’t get incredible service but that’s fine, because it’s casual,” he says, carefully, giving the impression that this is something he thinks about a lot. “The food comes out a little late, but it’s fine, because it’s casual. The chairs are uncomfortable and the space is too loud, but that’s fine, because the restaurant is casual.” What really offends him is the idea of using casual as an excuse for mediocrity: “I think it’s this weird situation where things that are nice are being degraded because they’re too formal.”

McGarry has been unusually obsessed with this idea lately because, just over two months ago, he opened his first restaurant. Gem, which serves just 32 people per night across two seatings (6 p.m. and 9), offers a tasting menu of 12-to-15 tiny, beautiful courses that are cooked, plated, and served with excruciating care. The vibe is Scandinavian, the furniture is heavily mid-century, topped with architectural arrangements of fresh flowers in thick vases, and the net effect is that you are eating dinner amid the world’s hippest production of Hedda Gabler. It’s not casual. But also it’s not too fancy? “In the seven weeks that we’ve been open, we’ve been three different restaurants,” McGarry says, and he knows with near-religious certainty that it is both necessary and correct. “Everyone’s like, you’re a month old, it’s fine,” he says. “To me, fine is like, the worst thing someone could say.”

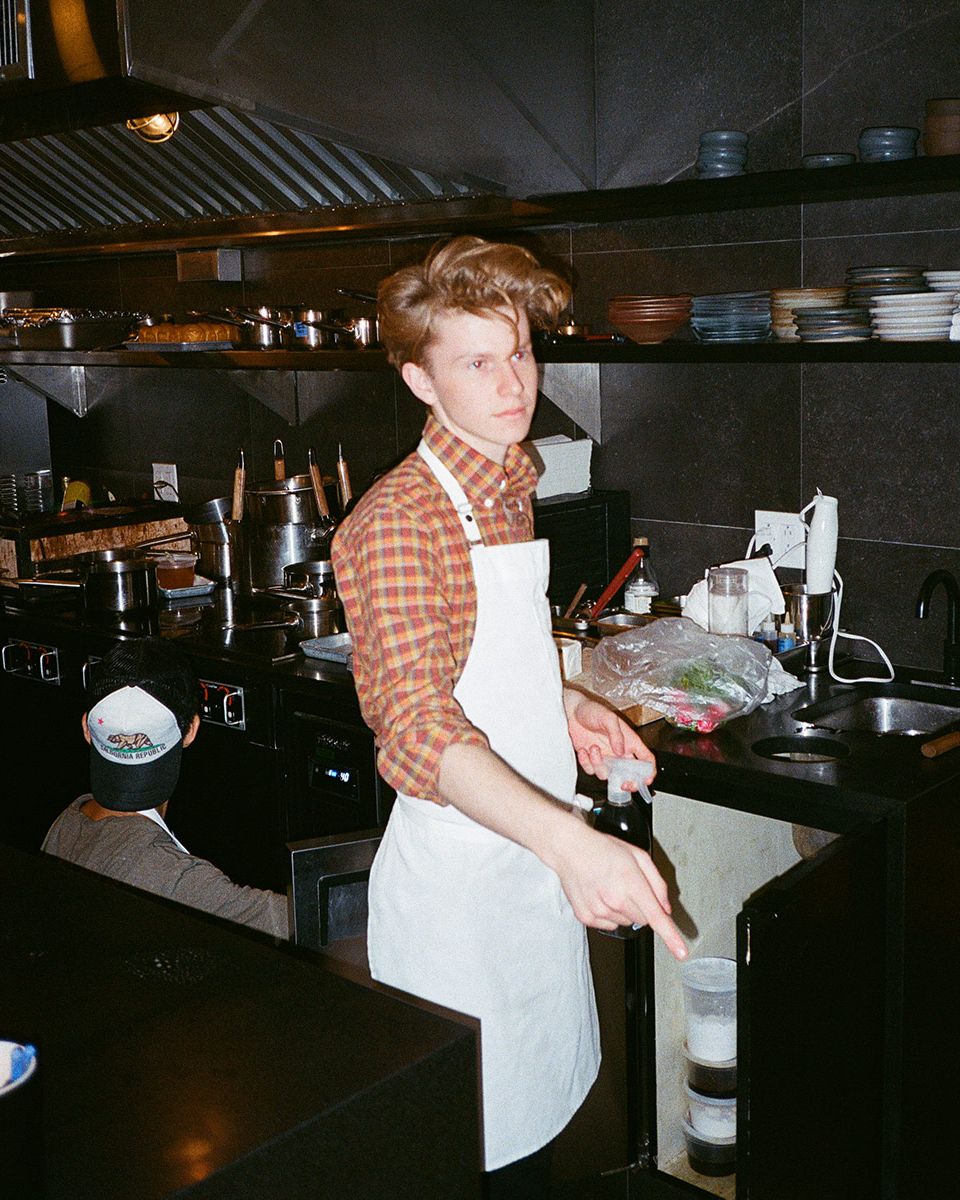

The problem with knowing so clearly what you like is that it makes it impossible to tolerate anything you don’t. “I couldn’t live with the fact that the tables were a little bit uncomfortable and not the right size,” he laughs, very seriously. “That kept me up at night.” So, he changed some tables, and adjusted the dining room’s traffic patterns. He tweaked the lighting and the playlist. In the kitchen, which is open to the dining room, his trio of cooks used to wear white button-up shirts with white aprons, he explains. Certainly, I could not have told you this. During my meal at Gem, I was focused on other things, like the beet-on-beet with beet bordelaise, a dish featuring beets that have been through an odyssey of preparations to expose the wine-dark depths of their fundamental beet-ness. But the cooks’ outfits, let McGarry tell you, were all wrong. So now they wear olive aprons and heavy white T-shirts from Uniqlo. They are nice T-shirts. Substantial. Good weight. These T-shirts weren’t even McGarry’s first choice, but you have to make compromises, that’s the thing about entrepreneurship. To hear him detail all of the anxiety that went into choosing them is to know that the decision to dress his cooks in T-shirts was most definitely not made casually.

Now would be a good time to note that McGarry is 19 years old. He has spent his entire career (seven years, give or take) known to the world as the Teen Chef. Vogue once called him “the Justin Bieber of food,” and the label stuck. Being compared to Justin Bieber may feel like a dubious honor, even for Justin Bieber, but McGarry has already achieved a level of recognition that many, much older chefs will simply never realize. And now he is in New York, with his first real restaurant and a built-in expiration date for his entire Teen Chef identity (he turns 20 on November 25), which means McGarry is at a point where people expect him to either make good on his promise as a brightly burning culinary star, or to suffer a Bieber-like meltdown, when he was peeing in mop buckets and surrendering his pet monkey to Germany.

McGarry doesn’t want a monkey. What he wants, all he’s ever wanted, is to run an elite restaurant, and he’s built an entire life in pursuit of that goal.

“A lot of people talk but don’t walk the walk,” says Esben Holmboe Bang, the chef and owner of Restaurant Maaemo in Oslo, the three-Michelin–starred restaurant where McGarry staged when he was 16. “If you want to have success, you have to dig in and sacrifice for it, at the end of the day; stay true, do good things and good things will come. Flynn has talent and determination. He will have success.”

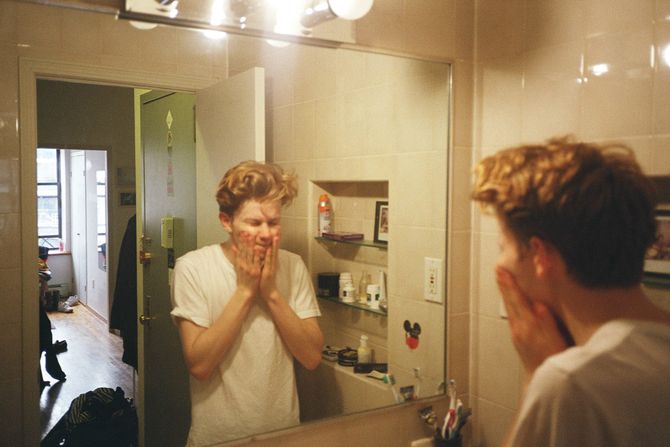

McGarry is wispily boyish, with orange hair so artfully tousled it’s sculptural, as though it has been inspired equally by James Dean and a crested penguin. By his own calculations, he is 31 in working years because he’s been singularly focused on cooking since he was 12, and, “Say someone figures out what they want to do in their mid-twenties, maybe 24,” he explains. “I’ve had a seven-year career of figuring that stuff out” and so he is now at a point in his career where that hypothetical 24-year-old will be when he becomes 31. It’s a complicated calculation that borders on philosophy — what is age? — but look, the point is, McGarry doesn’t feel 19: “I’m not led by my age; I’m led by what I do.”

If McGarry’s talent is his own, his success has been a family project. McGarry’s mother, Meg — “Gem,” forwards — is a writer and filmmaker, and his father, Will, is a photographer, and so his childhood was both artistic and extraordinarily well-documented. When he was 4 and his sister Paris was 8, the family moved to a Boho-chic trailer park, “where all these artists and surfers live” by the beach in Malibu, “because they thought it was a really nice place to grow up.” For a while, in elementary school, he wanted to be a rock star, and for a while after that he wanted to be a painter. If he was good at both, he wasn’t freakishly talented at either, and that pained him. “I was like, I don’t see this going anywhere. What’s the point?” he says, recalling a time when he was 8, which, if you think about it, was not all that long ago. But he was not wrong, exactly. It’s not like Bobby Fischer had a casual interest in chess.

When McGarry was 10, the family moved from the beach to Studio City. His dad went to rehab. His parents got divorced. His father had been the cook in the family, but his father wasn’t there, and his mother wasn’t into it, and McGarry was tired of the Whole Foods hot bar, so he took over dinners and found an escape. “I was so, so, incredibly obsessive about it,” he says. Everything else just sort of melted away. “I stopped caring about school, I just stopped caring about anything other than this one little thing.”

His mom had “so much to deal with, she was just like, ‘Sure, keep going.’ It made me happy. She didn’t have to deal with me being really depressed.” By 11, he had fallen in love with The French Laundry Cookbook, which he picked out from the bookstore because it was “on the top of the shelf and was kind of expensive.” Eventually, that led him to Grant Achatz’s Alinea cookbook, which McGarry discovered because he’s “really good at Googling.”

Here are some recipes from the Alinea cookbook that a person could, theoretically, make: surf clam with nasturtium leaf and flower and shallot marmalade; “transparency of Manchego cheese”; and venison encased in savory granola. It is not exactly a cookbook for beginners.

McGarry liked the Alinea book even more than The French Laundry. He liked it so much that he burrowed inside of it: He and his father built a kitchen in his childhood bedroom, based on YouTube videos of the kitchen at Alinea. Critics have jumped on this: the Austin Chronicle summed up McGarry’s life as “a rich kid who played restaurant with real ingredients, and turned out to be really, really good at this cooking thing.” Slate once declared, “Want Your Kid to Be a Celebrity Chef? You Better Have a Lot of Money.” But the bedroom kitchen is not, McGarry wants me to understand, evidence of some sort of vast wealth: “The basic setup in the bedroom probably cost $200. We bought a bunch of wood and built some tables.” The equipment dribbled in on Christmases and birthdays. “The most expensive thing I had in that kitchen was a $300 sous-vide thing. And that was like, my grandma and my dad and my mom and friends all pitching in.”

They started charging for the dinners, mostly because they couldn’t afford not to charge for the dinners: “My mom just couldn’t afford to keep fronting the bill for me to want to make some new dish every day.”And it still rankles him, that people assume he was born with a hand-forged egg spoon in his mouth. “It’s been absurdly misconstrued,” he concludes. And okay, yes, some money was involved. He had a private bedroom kitchen (even if it was a thrifty bedroom kitchen); his creative-class parents had a cadre of friends willing to spend serious money and help spread the word about dinners cooked by a talented kid; he flew across the country to stage with Daniel Humm at Eleven Madison Park. But whatever got spent was an investment in encouragement, a mother’s sacrifice for her family. At the same time, Meg was taking care of her parents, and had taken out a loan to send Paris to college. “My dad was in rehab, he wasn’t working, and my mom wasn’t really getting work,” McGarry says of that time. “She can’t ever get another AmEx card again. She had to go bankrupt, literally, because of this. And that instability made all of this possible.”

With Meg as de facto front-of-house, he started cooking his elaborate, eight- or ten-course tasting menus, first for friends and family and then for strangers. In 2012, The New Yorker ran a Talk of the Town piece under the headline “Prodigy” about the then-13-year-old; by then, McGarry, who’d been bullied at school, was homeschooling online and the pop-up charged $50 a head for dinner. Christopher Noxon, who wrote the piece, first heard about McGarry from his sister, who had heard about him from a Los Angeles pastry chef. There was “something just fascinating about the conditions of genius, about this kind of dysfunction that allowed for him to develop as an artist,” Noxon says. “It was a little creepy, in that his family all called him ‘chef,’ and clearly he was running the show. And they were all committed to helping him create this reality.” Plus the food. The food, truly, was special. “There were a couple of dishes where you have that sense of, ‘Holy shit, this is the best thing I’ve had in my mouth.’”

If Meg had said no, then it would have stopped there, one article, the end. But she didn’t. “I always make that joke,” she says, “that in the kitchen, you say, ‘Oui, chef’ when they call out an order, and somehow, that’s what I was doing during that period of time.” So the Teen Chef kept at it. Two years later, he was in chef’s whites on the cover of The New York Times Magazine’s Food Issue.

When he was 16, he opened his first pop-up in New York, inspiring a new wave of attention, not all of it positive. Chef David Santos, whose restaurant at the time had just closed, took to Instagram: “The fact the media even calls him a chef offends me to no end,” he wrote. “Chef is something you earn through years of being beaten and shit on and taught by some of the greats.” Had McGarry been shit on enough? It was a valid question, but the Teen Chef just kept at it. This winter, documentary filmmaker Cameron Yates’s Chef Flynn premiered at Sundance: “I don’t think any of this would have happened if I had a very motherly mom,” McGarry says in the film, “because there’s a huge part of it that’s just letting me go and do my own thing.”

When McGarry was still a 15-year-old culinary wunderkind in Los Angeles, he announced to The New York Times Magazine that he planned to open his own restaurant in New York by 19. Last November, four days after his birthday, he signed the lease for Gem. (Technically, he co-signed the lease on Gem with his sister, Paris, who is the legal owner of the restaurant, because he needed someone over 21 to get a liquor license, and Paris is 23.) Gem has “around 15” investors, some of whom were fans of the pop-ups, some of whom are “business people,” and some of whom didn’t know McGarry at all but had friends that did. Most of them have never invested in a restaurant before: “Investing in a restaurant like this is a bet, and the odds are low — it’s not an easy investment, and that’s why I got a bunch of people that are really trusted for smaller amounts of money,” McGarry says, “so they’d be less mad if they lost something in the ballpark of 20 grand.”

McGarry still has that original copy of the Alinea cookbook. It’s in his apartment, which is on the Lower East Side, four blocks from Gem. The apartment also contains: a bed. He used to have a palm tree, but it was sacrificed for the restaurant — he needed the pot — and now all that remains is a single browning frond to remember it by. He built a dining-room table, but ditched it when he realized he doesn’t actually have any dinner parties. Besides, the idea behind Gem is that a meal there is supposed to feel like a dinner party, which it kind of does, although it’s hard to shake the feeling — watching McGarry intently tweeze a 12-course tasting menu — that the chef is also being presented for the dining room to coolly ogle, like a rare panda on display at a very exclusive zoo.

For nearly half his life and all of his career, McGarry has been singular, the only one of his kind, an endangered species. If he wasn’t learning in someone else’s kitchen, he was working alone. And so it was the Teen Chef against the world, and he liked it that way. It was romantic. And now it is … less so.

At Gem, McGarry manages a team of 11, most of whom are almost as young as he is. “They’re all great, but I have those feelings every once in a while of, like, this would be better if I just did everything.” But he can’t do everything, so he has to communicate his vision to someone else, and live with the outcome. “If a painter was like, ‘Here’s the painting, you guys do it, and then we’re going to sell your painting for the same price as mine, and it will get reviewed the same way, but under my name’ — it’s fucking stressful.” You try telling somehow how to slice and fry a baby artichoke so it blossoms like a highbrow Bloomin’ Onion, and then, on top of it, arrange a small menagerie of herbs and not one but two different butter-smooth purees.

This is also not, you may have noticed, the golden age of $155 tasting menus — which is the type of dinner that Gem offers exclusively. Tasting menus are not particularly cool. “At first I had wanted him to do small plates, à la carte,” Paris tells me, “but I realized why the tasting menu makes so much sense.” Part of it, she suggests, is that tasting menus are fun. You can experiment with so many flavor combinations and techniques, all in the same meal, and get immediate feedback on all of it, because everyone’s eating the same thing. But also, tasting menus afford McGarry a kind of control. You know exactly how many people are coming, and what they’re going to eat, and how much it’s going to cost. There is no night when everyone suddenly orders the lobster and you run out, because there is no night when anyone orders anything other than a dinner cooked by Chef Flynn. “You can be incredibly prepared,” Paris says. “Everything is meticulous.”

The other thing about opening a restaurant when you are 19 and kind of famous, and maybe have not, let’s say, endured certain life experiences, such as “working for a decade in other people’s kitchens” or “turning 20,” is that the public does not necessarily approach your venture with great generosity. “Everyone’s expecting us to fail,” McGarry lays out, frankly. “People expect me not to be as good as everyone else, because I’m young or whatever. So we need to now work five times harder than everyone else. We don’t have the opportunity to just be good.”

The night I went to the restaurant — its second week in business — the women on one side of me took selfies with McGarry, while the women on the other tapped at their Parker House rolls with spoons to see if they were Parker House-y enough. An ideal Parker House roll, according to the apparent roll expert next to me, should make no noise when tapped. I didn’t tap mine, but I liked it.

McGarry could have waited to open his restaurant, obviously. Maybe it would have been better if he’d waited — even he’s not ruling that out. He could have held off, and gone to work in a kitchen “like literally everyone told me to go do.” But if he’d done that, he says he “would’ve felt weird,” like he wasn’t living up to his full potential. None of McGarry’s personal galaxy of Michelin-caliber colleagues actively discouraged him from opening now, but even if they had (which they didn’t), advice only tells you so much: “I’m the one that has to deal with this. I should have a say in it. And yeah, if that’s completely wrong, it’s completely wrong, but at least I feel like I’m doing what I want to be doing.”

A few days before our (not casual) lunch at the Four Horsemen, Gem received its first proper review, from The New Yorker. It read, in part, “Gem is decidedly mature, the kind of place where most young people would go only if their parents were paying.” McGarry was thrilled. “It wasn’t about, ‘This is a kid who’s doing this great thing,’” he says. “It was, ‘This is a really good restaurant.’” It’s the first time, in his mind, that his food has been written about like that, which is to say, like food cooked by an adult, not food cooked by a teenager.

All Flynn McGarry has ever wanted was a restaurant, and now he has a restaurant, and it’s strange, isn’t it, to live through the last moment you ever imagined. If Gem is wildly successful, with all the stars — critics’ stars and Michelin stars and how about five Yelp stars for good measure — then what happens? Or what if this whole thing is a disaster? “That would validate every bad thing anyone’s ever said about me, and it would make everyone else right,” McGarry says. “For six years, everyone’s been writing ‘the prodigy,’ these very lofty words about me. Then it would be ‘the prodigy failed.’” But he understands! He’s not mad! He has a much more mature outlook on all of this than most people who are seven months shy of their 20th birthdays: “I’ll do everything in my ability to make it not fail, but if it does fail — I’ll figure it out. I don’t think I’ve ever been that comfortable with not really knowing what’s next, and I’m kind of fine with that.”

*A version of this article appears in the May 14, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!